Healthy Skepticism Library item: 2166

Warning: This library includes all items relevant to health product marketing that we are aware of regardless of quality. Often we do not agree with all or part of the contents.

Publication type: news

Demoro D.

The nursing shortage & the drug connection.

Revolution 2001 Jun

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12018055

Full text:

Business gurus tout the recent wave of large pharmaceutical industry mergers and acquisitions as a way to lower drug costs. With competing companies merging their R&D efforts, drug companies will enjoy “economies of scale,” which, according to experts, should maximize their ability to develop new drugs and bring them to market. Administrative expenses, once performed in each company, would be combined into one and further reduce expenses. So consumers would get more and better prescription drugs at lower prices.

Business gurus tout the recent wave of large pharmaceutical industry mergers and acquisitions as a way to lower drug costs. With competing companies merging their R&D efforts, drug companies will enjoy “economies of scale,” which, according to experts, should maximize their ability to develop new drugs and bring them to market. Administrative expenses, once performed in each company, would be combined into one and further reduce expenses. So consumers would get more and better prescription drugs at lower prices.

That’s the business theory. In practice, just the opposite is happening.

Pharmaceutical industry mergers appear to be a primary cause of the explosive rise in prescription drug costs and may be a key factor in influencing hospitals to reduce hospital nurse staffing levels.

Pharmaceutical industry mergers appear to be a primary cause of the explosive rise in prescription drug costs and may be a key factor in influencing hospitals to reduce hospital nurse staffing levels.

That’s the findings of a study just completed by the Institute for Health and Socio-economic Policy (IHSP). Through the study, conducted at the request of Rep. Dennis J. Kucinich (D-Ohio), the IHSP was able to document for the first time a correlation among patient access, corporate market share activities, and health caregiver staffing ratios.

At the heart of the 125-page study is an analysis of the staggering economic and social effects of the pharmaceutical industry merger and acquisition binge of recent years – augmented by a survey of hospital executives who describe their response to prescription drug price hikes.

The findings should send a sobering message to policy makers: Hospitals expect to lay off nurses in the midst of a national hospital nursing shortage and Medicare patients may have even less access to needed prescription drugs. Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry becomes dominated by a handful of corporate giants who are making record profits.

The findings should send a sobering message to policy makers: Hospitals expect to lay off nurses in the midst of a national hospital nursing shortage and Medicare patients may have even less access to needed prescription drugs. Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry becomes dominated by a handful of corporate giants who are making record profits.

The study also uncovered another trend: Escalating drug prices – not reductions in Medicare reimbursement rates, as many contend – may be the primary culprit in lower revenues and profits for many hospitals and managed care plans. Hospitals have responded by cost-cutting, in the form of staffing cuts and service reductions.

While all health care consumers feel the pinch of staffing cuts, seniors bear the brunt of rising drug prices. As the biggest consumer of prescription drugs, seniors with employer-provided retiree health plans face cost-shifting by their former employers. Those without coverage have it even worse, as they have no stepladder to reach the drug costs that climb out of reach.

Survey is revealing

While the IHSP research drew from many sources, a key element is the phone survey of hospital executives. Hospital administrators or finance managers were asked if they thought mergers in the pharmaceutical industry would lead to high prices and if pharmaceutical price increases pressure his or her hospital to reduce staff-to-patient levels, as well as several other questions. Rep. Kucinich’s office conducted the phone survey, contacting 100 targeted hospitals across the United States, selected to assure an appropriate geographic, urban and rural balance.

Overall, 68 percent of the hospital executives – and more than three-fourths of Midwestern and Southern respondents – indicated that current staffing levels are put at risk by increases in drug prices. In the current context of an already woefully inadequate caregiver staffing level, such assessments by high-level hospital administrators may portend a clear and present danger to the public health that the nation can ill afford to ignore.

Many administrators publicly concede that increases in drug prices may lead to future reductions in patient-to-staff ratios, despite the nationwide nursing shortage that sees no foreseeable end in sight. If hospital executives currently feel that they may reduce staffing ratios due to increased drug prices, it seems a reasonable assumption that drug prices may have been a significant factor in past hospital industry decisions to lay off caregiver staff.

Unfortunately, drug prices are on the rise. This year they’re expected to increase 17.5 percent.

Most commonly used drugs are going up at twice the rate of inflation. The impact on hospitals will be considerable, given that in 1999 drug spending accounted for 44 percent of the increase in health costs, according to a report in Health Affairs.

Relaxed anti-trust laws fuel binge

Drug cost increases were not always the norm. Prescription drugs, as a percentage of total health care costs, were flat from 1990 through 1994, sitting squarely at 5.8 percent of costs. However, in 1995, the figure moved up to 6.4 percent and continues to rise. In 1998, prescription drugs as a percentage of total health costs had risen to 7.4 percent, and in 1999 it was 8.2 percent.

No surprise that 1994 marks the change in the Sherman Act, which granted extraordinary latitude to merging health care corporations, reputedly to encourage competition and lower prices. (Ironically, changing the antitrust law was the only major change adopted by Congress in response to the Clinton administration’s 1993 health care plan.)

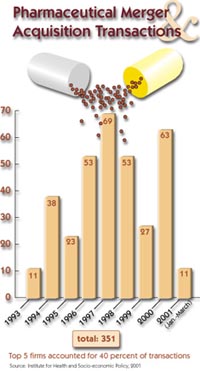

Relaxing the law brought about consolidation, but not competition. The 227 publicly reported pharmaceutical merger prices since 1993 add up to a cost of $270 billion in year 2000 dollars, enough money to pay for about 70 percent of the annual total costs for all inpatient hospital care in the United States.

In fact, the total cost of about $270 billion is an extremely conservative figure. Of the 351 total transactions, only 227 or about 65 percent of them had publicly announced prices. The price of the other 124 transactions, or 35 percent of the total transactions, is unknown. A simple averaging of transactions costs would imply another $100 billion should be added to the $270 billion total.Today, 50 firms control two-thirds of the world pharmaceutical market, and the top 10 U.S. companies make up about 40 percent of the domestic market. Publicly traded pharmaceutical firms with more than $1 million in net sales totaled more than $411 billion in total net sales and $43.6 billion in profits last year.

All this merger activity is having extraordinary market impact. Five of the 10 most powerful marketers in the industry recently merged. The list includes GlaxoSmithKline, created in December 2000 when Glaxo Wellcome joined with SmithKline Beecham; Pfizer, which took over Warner-Lambert in June 2000; Pharmacia, formed by the union of Pharmacia & Upjohn and Searle in April 2000; AstraZeneca, created by the 1999 merger of Astra AB and Zeneca; and Aventis, launched in 1999 through the union of Hoechst Marion Roussel and Rhone-Poulenc Rorer.

These five new entities accounted for more than 35 percent of all promotional spending by the pharmaceutical industry in 2000, according to Scott-Levin’s marketing research audits. They also generated more than 30 percent of all retail sales, reports Scott-Levin’s SourceTM Prescription Audit.

Overall, the top 10 companies were responsible for 66 percent of the industry’s promotional spending and 58 percent of retail prescription sales.

Pharmaceutical companies are now the most profitable business in the country, according to Forbes magazine. CEOs of 12 drug companies averaged $22 million in compensation in 1998. Huge tax benefits allowed drug companies to lower their tax rates by nearly 40 percent, relative to all other major U.S. industries between 1990 and 1996. Federal subsidies substantially reduced industry’s costs for R&D.

Stoking consumer demand

The industry has thrown another log on the fire fueling the rise in prescription drugs as a percentage of total health costs. That log is the massive increase in pharmaceutical marketing and advertising intended to stimulate consumer consumption. In 1999, the industry reported that promotional spending reached a record high $13.9 billion, an 11 percent increase over 1998.

Television advertising for drugs alone has jumped 20 percent since 1994. The $136 million just spent by Schering-Plough on advertising for Claritin in 1998 would have been sufficient to employ about 3,230 RNs.

Many heavily advertised drugs, particularly antihistamines, antidepressants and cholesterol reducers, are likely to be used on an ongoing basis. Spending on oral antihistamines such as Claritin, Zyrtec and Allegra increased by 612 percent between 1993 and 1998. Spending on antidepressants such as Prozac, Zoloft and Paxil increased by 240 percent between 1993 and 1998. Spending on cholesterol-reducing drugs such as Lipitor, Zocor and Pravachol increased by 194 percent between 1993 and 1998.

The 10 drugs most heavily advertised directly to consumers in 1998 accounted for $9.3 billion or about 22 percent of the total increase in drug spending between 1993 and 1998.

In 1998, only four major pharmaceutical firms accounted for about 22 percent of all pharmaceutical sales by major as opposed to generic pharmaceutical corporations, and eight firms accounted for 39 percent. However, with the advent of the Glaxo-Wellcome SmithKline and Pfizer Warner Lambert mergers, the top four major pharmaceutical firms now have close to a 30 percent market share among the major drug manufacturers.

Concentrations of sales for the top therapeutic categories are even more dramatic. Only four firms account for the vast majority of sales for some of the most commonly prescribed kinds of medications.

Managed care and PBMs

Managed care plans, hit with escalating drug costs, sought an answer and found it (or thought they had) in PBMs or pharmacy benefit management programs. PBMs typically select participating pharmacists and drug manufacturers and suppliers, create and administer a point-of-sale claims processing system, negotiate volume discounts with pharmaceutical manufacturers, administer the record keeping and payments, and maintain quality control. Over 135 million Americans currently receive benefits through PBMs, and that number is expected to increase to 200 million by the end of the decade.

The first PBMs were guided by an independent panel of physicians and therapists who used objective criteria to select drugs in an open formulary. PBM managers “shopped” drug companies to set up volume discount pricing that would be advantageous to their members (and company). Merck & Co., the largest pharmaceutical firm in the world with $32.7 billion in sales, offers Merck-Medco PBM.

As pharmaceutical corporations consolidate and gain market power, they are more easily able to set higher drug prices. After stoking consumer demand for brand-name drugs, drug companies offer their products to U.S. consumers at twice the cost of the same drug in Canada, Mexico and England, 75 percent more than in France and 100 percent more than in Italy.

Exit market, stage right

Once hospitals and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) incurred the effects of the mushrooming drug costs, they readily passed the pain along to their respective patients and plan members.

Though aggregate hospital profits have totaled about $178 billion since 1986, they have declined the past two years. A number of hospitals, especially small, independent hospitals now are experiencing financial distress. Many have closed or scaled back services, requiring patients to wait longer for access to care.

In the early 1990s, HMOs were aggressively recruiting Medicare recipients, with an emphasis on the healthiest and wealthiest patients. That practice has sharply reversed course with increasing numbers of HMOs deserting the Medicare market. In the lead is giant Aetna, which exited 11 states and 23 counties in three other states and affected 355,000 members – more than half of the company’s market share.

Of course, cash-strapped public hospitals fare the worst. Not only must they contend with rising drug costs, the reduction in Medicare payments has pushed many toward (or into) red ink.

Conversely, the Medicare reimbursement reductions have not trounced the hospital industry as the industry has claimed. On the eve of an $11 billion funding increase for Medicare and Medicaid payments in late 2000, a congressional advisory board announced that hospitals still received a 12 percent Medicare impatient margin and 5.9 percent overall Medicare profit margin in 1999.

Seniors suffer

Seniors have borne the biggest brunt of the pharmaceutical industry merger binge and rising drug costs. Elderly Americans consume 28 percent of all prescription drugs, and 20 percent of seniors take at least five prescription medications daily.

The average drug cost for each senior citizen in 1999 was more than $1,200, and that is expected to rise to over $2,800 per person by 2010. Some 13 million Medicare beneficiaries have no prescription drug coverage, and seniors, as a group, tend to fill one-third fewer prescriptions and pay twice as much out-of-pocket costs as other population groups.

Medicare beneficiaries – many of whom are being deserted by the HMO industry – comprise the single largest patient group in need of expensive medications. Those beneficiaries are at particular risk to increases in drug pricing structures. Only 53 percent of Medicare beneficiaries had drug coverage for the entire year of 1996. Medicare+Choice plans generally have reduced drug benefits and increased enrollee out-of-pocket costs in 2000. Eighty-six percent of plans have annual dollar limits on drugs.

One employer survey recorded a drop in the number of large firms offering health benefits to Medicare-eligible retirees – from 40 percent in 1993 to 28 percent in 1999. Additionally, employers have tightened eligibility rules and increased cost-shifting to retirees. Of those employers that still offer medical coverage, the survey found that 40 percent are requiring Medicare-eligible retirees to pay for drug coverage.

Individuals with incomes between 100 percent and 150 percent of poverty, or individuals age 65 or older with incomes between $7,527 and $11,287 in 1996, have the lowest rate of coverage.

Lean and mean

Despite the impact rising drug costs have on seniors, other consumers and health care providers, the pharmaceutical industry boldly defends mergers. That “economies of scale” model posited means the new company can devote more resources to R&D in a leaner, more efficient post-merger environment. The industry estimates that the average cost of developing a successful drug is more than $500 million.

The accuracy of that estimate is not universally shared. Other experts say that the $500 million per drug estimate is inflated, and is based on confidential industry data not subject to outside review. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in 1998, the industry spent three times as much on marketing and administrative expenses than on R&D as a percentage of sales.

Whatever the cost of drug development, the drug industry burden in those costs is considerably lightened through federal subsidies. A 1995 study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that, of the 14 new drugs the industry identified as the most medically significant in the preceding 25 years, 11 had their roots in studies paid for by the government.

In a 1997 study commissioned by the National Science Foundation, C.H.I. Research looked at the most significant scientific research papers cited in medicine patents. It found that half the cited studies were paid for with public funds, primarily from government and academia; only 17 percent were paid for by the industry.

Although drug companies claim mergers will improve the industry’s success in health breakthroughs, another industry expert is not buying it. Dr. Sidney Wolf, director of public health group for Public Citizen, said, “There is no evidence that the economies of scale have resulted in price savings to consumers – quite the contrary. Also, there is no evidence that more research will come out of the combined companies than the two individual companies.”

Cut to the bone

Drug price increases may have played a significant historical but overlooked role in generating the current nursing shortage as the provider sector embarked upon ill-conceived restructuring programs – programs that placed reduced numbers of caregiver staff at the core of their design models – offered by the management consulting industry.

Many U.S. hospitals are not about to reduce any income that might be coming their way. As the phone survey proved, hospital executives see a correlation between the mergers leading to higher drug prices and higher drug prices leading to cost-cutting measures.

Hospitals have traditional ways of cost cutting. One is simply to close. Another is to close the emergency room, which means care to the uninsured likely will deteriorate, since the emergency room is their primary route to care. And a highly popular method of reducing expenses is reducing staff.

Nurses, health care workers, patient advocates and patients already know the fragile state of patient care in U.S. hospitals. Further staff cuts could decimate, totally and ultimately, the health profession’s creed of “first, do no wrong.”

Re-balancing the economies of scale would be a Herculean task. Educating the media and the public, pushing facts in front of lawmakers, and speaking out on the harsh realities of the pharmaceutical industry are important first steps.

And maybe it all makes you wonder where the CEO of GlaxoSmithKline or Pfizer Warner Lambert goes when the heart cramps or bp spikes.

Don DeMoro is the director of the Institute for Health and Socio-economic Policy. The Institute for Health & Socio-Economic Policy (IHSP) is a non-profit policy and research group. Its focus is current political-economy policy analysis in health care and other industries and the constructive engagement of alternative policies with international, national, state and local bodies to enhance, promote and defend the quality of life for all.

For a copy of the complete study,

“Big Pharma:” Mergers, Drug Costs and Health Caregiver Staffing Ratios, in PDF format Click Here (Note, this report is 125 pages and 680kb in size)